Non-Parametric Analysis Of Variance

As we’ve seen in the last few posts, linear models can be successfully applied to many data sets. However, there may be times when even after transforming variables, your model clearly violates the assumptions of linear models. Alternatively, you may have evidence that there is a complex relationship between predictor and response that is difficult to capture through transformation. In these cases, non-parametric regression techniques offer alternative methods for modeling your data.

Non-Parametric ANOVA

One of the assumptions of parametric ANOVA is that the underlying data are normally distributed. If we have a data set that violates that assumption, as is often the case with counts (especially of relatively rare events), then we’ll need to use a non-parametric method such as the Kruskal-Wallis (KW) test.

The setup for the KW test is as follows:

- Level 1: $X_{11}, X_{12}, …,X_{1J_{1}} \sim F_{1}$

- Level 2: $X_{21}, X_{22}, …,X_{2J_{2}} \sim F_{2}$

- …

- Level I: $X_{I1}, X_{I2}, …,X_{IJ_{I}} \sim F_{I}$

Null hypothesis $H_{o}: F_{1} = F_{2} = … = F_{I}$

Alternative hypothesis $H_{a}:$ not $H{o}$ (i.e., at least two of the distributions are different).

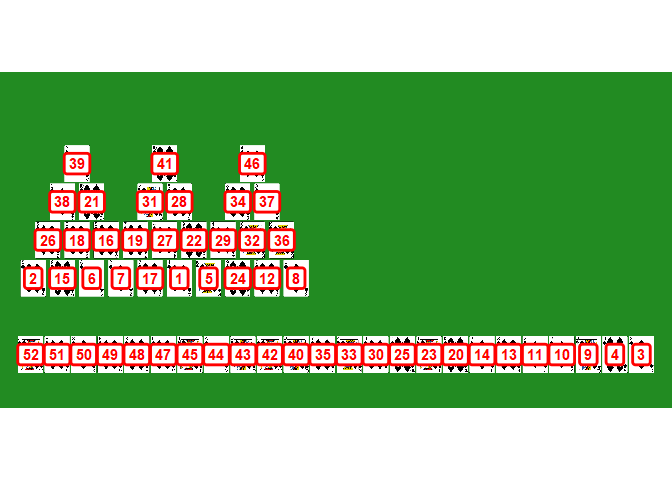

The idea behind the KW test is to sort the data and use an observation’s rank instead of the value itself. If we have a sample size $N = J_{1}, J_{2}, … J_{I}$, we first rank the observations (the lowest value gets a 1, second lowest a 2, etc.). If there are ties, then use the mid-rank (the mean of the two ranks). Then, separate the samples into their respective levels and sum the ranks for each level. For example, if we have three levels:

- Level 1: $R_{11} + R_{12} + … + R_{1J_{1}}=$ sum of ranks

- Level 2: $R_{21} + R_{22} + … + R_{2J_{1}}=$ sum of ranks

- Level 3: $R_{31} + R_{32} + … + R_{3J_{1}}=$ sum of ranks

Now we do the non-parametric equivalent of a sum of squares for treatment (SSTr) using these ranks. The KW test statistic takes the form:

\[K=\frac{12}{N(N+1)}\sum\limits_{i=1}^{I}{\frac{R^2_{i}}{J_{i}}-3(N+1)}\]For hypothesis testing, we calculate a p-value where large values of K signal rejection. We do this by approximating K with a chi-square distribution having $I-1$ degrees of freedom. According to Devore1, chi-square is a good approximation for K if:

- If there are I = 3 treatments and each sample size is >= 6, or

- If there are I > 3 treatments and each sample size is >= 5

Let’s look at an example. Say we are a weapon manufacturer that produces rifles on three different assembly lines, and we want to know if there’s a difference in the number of times a weapon jams. We select 10 random weapons from each assembly line and perform our weapon jamming test identically on all 30 weapons. I’ll make up some dummy data for this situation by drawing random numbers from Poisson distributions with two different $\lambda$s.

library(tidyverse)

set.seed(42)

j = c(rpois(10, 10), rpois(10, 10), rpois(10, 15))

r = rank(j, ties.method="average")

l = paste("line", rep(1:3, each = 10), sep="")

tibble(

jams1 = j[1:10],

rank1 = r[1:10],

jams2 = j[11:20],

rank2 = r[11:20],

jams3 = j[21:30],

rank3 = r[21:30])

## # A tibble: 10 x 6

## jams1 rank1 jams2 rank2 jams3 rank3

## <int> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <int> <dbl>

## 1 14 19.5 14 19.5 8 3.5

## 2 8 3.5 17 27 21 30

## 3 11 10.5 5 1 16 23.5

## 4 12 13.5 14 19.5 16 23.5

## 5 11 10.5 13 16 13 16

## 6 9 6.5 12 13.5 18 29

## 7 14 19.5 11 10.5 17 27

## 8 9 6.5 13 16 11 10.5

## 9 16 23.5 7 2 16 23.5

## 10 9 6.5 9 6.5 17 27

For this data,

- $I = 3$

- $J_{1} = J_{2} = J_{3} = 10$

- $N = 10 + 10 + 10 = 30$

- $R_{1} =$ 120

- $R_{2} =$ 131.5

- $R_{3} =$ 213.5

Which gives the K statistic:

\[K=\frac{12}{30(31)} \left[\frac{120^2}{10} + \frac{131.5^2}{10} + \frac{213.5^2}{10}\right] - 3(31)\]K = 12/(30*31) * (sum(r[1:10])^2/10 + sum(r[11:20])^2/10 + sum(r[21:30])^2/10) - 3*31

print(paste("K =", K), quote=FALSE)

## [1] K = 6.70903225806452

Then, compute an approximate p-value using the chi-square test with two degrees of freedom.

1 - pchisq(K, df=2)

## [1] 0.03492627

We therefore reject the null hypothesis at the $\alpha = 0.5$ test level. Of course, there’s an R function kruskall.test() so we don’t have to do all that by hand.

rifles = tibble(jams = j, line = l)

kruskal.test(jams ~ line, data = rifles)

##

## Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test

##

## data: jams by line

## Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 6.7845, df = 2, p-value = 0.03363

Multiple Comparisons

The KW test can also be used for multiple comparisons. Recall that we applied the Tukey Test to the parametric case, and it took into account that there is an increase in the probability of a Type I error when conducting multiple comparisons. The non-parametric equivalent is to combine the Bonferroni Method with the KW test. Consider the case where we conduct $m$ tests of the null hypothesis. We calculate the probability that at least one of the null hypotheses is rejected ($P(\bar{A})$) as follows:

\[P(\bar{A}) = 1-P(A) = 1-P(A_{1} \cap A_{2} \cap...\cap A_{m})\] \[=1-P(A_{1})P(A_{2})\cdot\cdot\cdot P(A_{m})\] \[=1-(1-\alpha)^{m}\]So if our individual test level target is $\alpha=0.05$ and we conduct $m=10$ tests, then $P(\bar{A})=1-(1-0.05)^{10}=$ 0.4012631. If we want to establish a family-wide Type I error rate, $\Psi=P(\bar{A})=0.05$, then the individual test levels should be:

\[\alpha=P(\bar{A}_{i})=1-(1-\Psi)^{1/m}\]For example, if $\Psi=0.05$ and we again conduct $m=10$ tests, then $\alpha=1-(1-0.05)^{1/10}=$ 0.0051162. The downfall of this approach is that the same data are used to test the collection of hypotheses, which violates the independence assumption. The Bonferroni Inequality saves us from this situation because it doesn’t rely on the assumption of independence. Using the Bonferroni method, we simply calculate $\alpha=\Psi/m = 0.005$. Note that this is almost identical to the result when we assumed independence. Unfortunately, the method isn’t perfect. As noted in Section 2 of this paper the Bonferroni method tends to be overly conservative, which increases the chance of a false negative.

Using the rifles data from earlier, if we wanted to conduct all three pair-wise hypothesis tests, then $\alpha=0.05/3=0.01667$ for the individual KW tests.

The dunn.test() function from the aptly-named dunn.test package performs the multiple pair-wise tests and offers several methods for accounting for performing multiple tests, including Bonferroni. For example (and notice we get the KW test results also):

dunn.test::dunn.test(rifles$jams, rifles$line, method="bonferroni")

## Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test

##

## data: x and group

## Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 6.7845, df = 2, p-value = 0.03

##

##

## Comparison of x by group

## (Bonferroni)

## Col Mean-|

## Row Mean | line1 line2

## ---------+----------------------

## line2 | -0.293738

## | 1.0000

## |

## line3 | -2.388222 -2.094483

## | 0.0254 0.0543

##

## alpha = 0.05

## Reject Ho if p <= alpha/2

According to the dunn.test documentation, the null hypothesis for the Dunn test is:

The null hypothesis for each pairwise comparison is that the probability of observing a randomly selected value from the first group that is larger than a randomly selected value from the second group equals one half; this null hypothesis corresponds to that of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank-sum test. Like the ranksum test, if the data can be assumed to be continuous, and the distributions are assumed identical except for a difference in location, Dunn’s test may be understood as a test for median difference. ‘dunn.test’ accounts for tied ranks.

-

Devore, Jay. 2015. “Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences”. 9th ed. Cengage Learning. ↩

Comments