Q-Learning

I’ve been reading some books on machine learning, and recently started going through Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow by Aurélien Géron. His chapter on reinforcement learning is great, and it inspired me to apply some of the methods on my own. I decided to start with the game of tic-tac-toe since it’s a little more complicated than a trivial simple example but not as complicated as chess or go.

States and Actions

Q-Learning is a type of reinforcement learning that can be applied to situations where there are a discrete number of states and actions, but the transition probabilities between states are unknown. In the game of tic-tac-toe, the state is the game board, which consists of nine possible locations to play that are either empty, contain an X, or contain a O. I will represent the state as an array of length nine where 0 represents an empty space, 1 represents an X, and -1 represents an O. I’m defining things this way because eventually I want to apply deep Q learning to the same problem, and these will become inputs to a neural network. Anyway, at the beginning of the game, the board is empty, so it will be represented as:

state = [0 for i in range(9)]

state

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

At the beginning of the game, there are nine possible actions for the first player (in this case, player X). An action of 0 represents X playing in the upper left board position, an action of 1 represents the upper middle position, etc. If X plays action 0, and O plays action 3, the state becomes:

state[0] = 1 # X plays action 0

state[3] = -1 # O plays action 3

state

[1, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Rewards

In all reinforcement learning techniques, a reward system is used. To develop a game playing policy for X, if an action results in X winning the game, the reward will be 1. If O wins, the reward will be -1. All other actions will have a reward of 0.

Q-Values

In Q-Learning, state-action pairs (s, a) have an associated quality value Q that are used to determine what the best move is for that state (the higher the Q-value, the better the move). When the algorithm begins and the first game is played, all Q-values are zero, so the AI (player X) is essentially playing randomly. Once the first game is played that is either a win or a loss, the first non-zero reward is given, and so the first non-zero Q-value is produced for the state-action pair that resulted in that reward. As the algorithm explores the state space, non-zero Q-values propagate back from the state-action pairs that won or lost the game to the state-action pairs that led up to the winning or losing move. In other words, the Q-values are slowly updated based on a running average of the reward r received when leaving a state s with an action a plus the sum of discounted future rewards it expects to get assuming optimal play from that point on and adjusted by a learning rate . To estimate the sum of the discounted future rewards, I take the maximum of the Q-value estimates for the next state s′. That was a mouthful. Maybe in this case, math might be clearer than English:

That’s it. It ends up just being a big book-keeping exercise to keep track of a whole bunch of state-action pairs and their associated Q-values. To do that, I use a dictionary data structure with the state-action pair as the key and the Q-value as the value.

Epsilon-Greedy Policy

I added an epsilon-greedy policy to encourage the algorithm to continue to explore the state-space throughout the training process. I implemented it in the following way. Before each action by X, I draw a random number and compare it to a variable represented by epsilon. If the random number is less than epsilon, then player X’s next action is random. Otherwise, player X’s next action is determined by the Q-values. When the algorithm starts, epsilon is 1.0. As training progresses, epsilon gradually decreases to 0.01.

The Tic-Tac-Toe Environment

I set this all up in a Python class called env with the following functions:

resetsets the state to represent an empty board (the start of a new game)game_overchecks to see if the game is over, and if so, gives a reward for a win or losssteprepresents a single action either by player X or player Otrain_qimplements the Q-learning algorithm

After importing the usual suspects, I define the env class.

import copy

import random

from IPython.display import clear_output

from bokeh.plotting import figure, show

from bokeh.io import output_notebook

from bokeh.layouts import column, row

output_notebook()

class env:

def __init__(self):

self.state = self.reset()

self.alpha0 = 0.05 # learning rate

self.decay = 0.005 # learning rate decay

self.gamma = 0.95 # discount factor

self.Qvalues = {}

def reset(self):

return [0 for i in range(9)]

def game_over(self, s):

done = False

reward = 0

if (s[0] + s[1] + s[2] == 3 or s[3] + s[4] + s[5] == 3 or s[6] + s[7] + s[8] == 3 or

s[0] + s[3] + s[6] == 3 or s[1] + s[4] + s[7] == 3 or s[2] + s[5] + s[8] == 3 or

s[0] + s[4] + s[8] == 3 or s[2] + s[4] + s[6] == 3):

done = True

reward = 1

if (s[0] + s[1] + s[2] == -3 or s[3] + s[4] + s[5] == -3 or s[6] + s[7] + s[8] == -3 or

s[0] + s[3] + s[6] == -3 or s[1] + s[4] + s[7] == -3 or s[2] + s[5] + s[8] == -3 or

s[0] + s[4] + s[8] == -3 or s[2] + s[4] + s[6] == -3):

done = True

reward = -1

if sum(1 for i in s if i != 0)==9 and not done:

done = True

return done, reward

def step(self, state, action, player):

next_state = state.copy()

if player == 0: next_state[action] = 1

else: next_state[action] = -1

done, reward = self.game_over(next_state)

return next_state, done, reward

def train_q(self, iterations):

for iteration in range(iterations): # loop to play a bunch of games

state = self.reset()

next_state = state.copy()

done = False

epsilon = max(1 - iteration/(iterations*0.8), 0.01)

while not done: # loop to play one game

if random.random() < epsilon: # epsilon greedy policy for player X

action = random.choice([i for i in range(len(state)) if state[i] == 0])

else:

xq = [self.Qvalues.get((tuple(state), i)) for i in range(9) if self.Qvalues.get((tuple(state), i)) is not None]

if len(xq) == 0: action = random.choice([i for i in range(len(state)) if state[i] == 0])

else:

idx = [i for i in range(9) if self.Qvalues.get((tuple(state), i)) is not None]

action = idx[xq.index(max(xq))]

next_state, done, reward = self.step(state, action, 0)

if not done: # random policy for player O

omove = random.choice([i for i in range(len(next_state)) if next_state[i] == 0])

next_state, done, reward = self.step(next_state, omove, 1)

if not done:

key = (tuple(state), action)

if key not in self.Qvalues:

self.Qvalues[key] = reward

next_idx = [i for i in range(9) if self.Qvalues.get((tuple(next_state), i)) is not None]

if len(next_idx) > 0:

next_value = max([self.Qvalues.get((tuple(next_state), i)) for i in next_idx])

else: next_value = 0

else: next_value = reward

# now update the Q-value for the state-action pair

alpha = self.alpha0 / (1 + iteration * self.decay)

self.Qvalues[key] *= 1 - alpha

self.Qvalues[key] += alpha * (reward + self.gamma * next_value)

state = next_state.copy()

return self.Qvalues

Results

The play_v_random function pits the AI-enabled player against an opponent that plays randomly. It takes the number of games to be played as an argument and returns the number of X wins, O wins, and ties.

def play_v_random (games):

results = [0 for i in range(games)]

for i in range(games):

state = ttt.reset()

next_state = state.copy()

done = False

while not done:

xq = [Q_values.get((tuple(state), i)) for i in range(9) if Q_values.get((tuple(state), i)) is not None]

if len(xq) == 0:

action = random.choice([i for i in range(len(state)) if state[i] == 0])

else:

idx = [i for i in range(9) if Q_values.get((tuple(state), i)) is not None]

action = idx[xq.index(max(xq))]

next_state, done, reward = ttt.step(state, action, 0)

if not done:

omove = random.choice([i for i in range(len(next_state)) if next_state[i] == 0])

next_state, done, reward = ttt.step(next_state, omove, 1)

state = next_state.copy()

results[i] = reward

return results

So here we go. I’ll have X play O before any Q-learning, update the Q-values based on 20,000 games, have X play O again, update Q-values some more, and so on for 10 iterations. By the end, the algorithm will have seen 200,000 games. Recall that the output is X wins, O wins, and ties and that X plays O 1,000 times, so move the decimal to the left once for the percent of wins.

ttt = env()

for i in range(101):

Q_values = ttt.train_q(2000)

if i % 10 == 0:

results = play_v_random(1000)

print(sum(1 for i in results if i == 1), sum(1 for i in results if i == -1), sum(1 for i in results if i == 0))

619 217 164

769 76 155

764 71 165

757 74 169

776 58 166

796 51 153

776 34 190

776 60 164

770 33 197

812 23 165

780 32 188

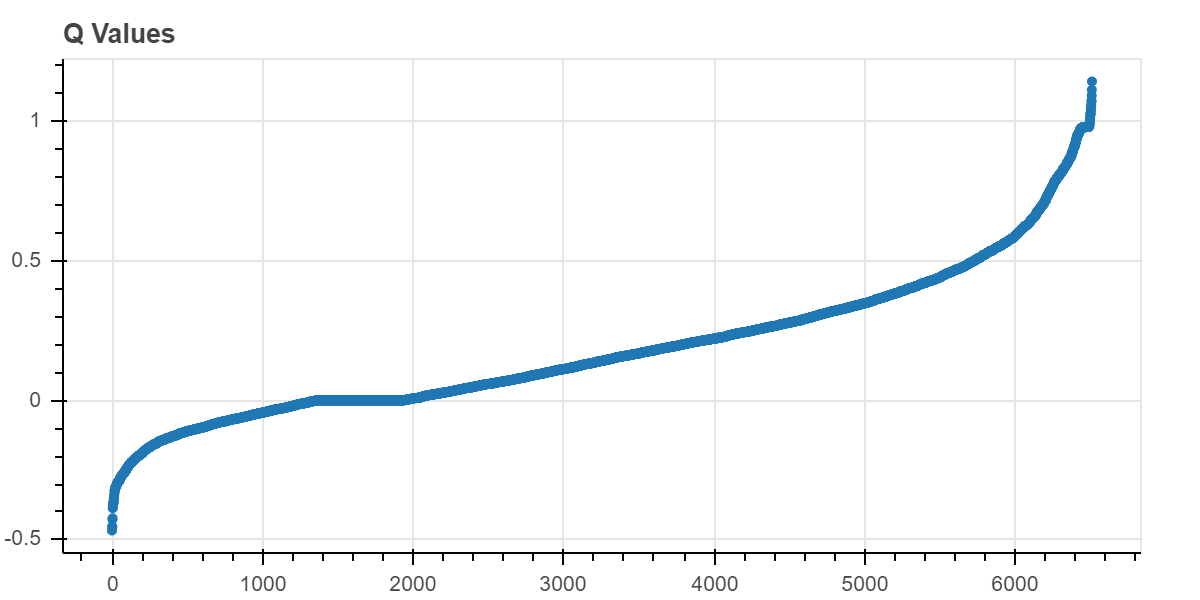

Seems to be working nicely! X, the AI-enabled player, definitely improves over time. This shows all of the non-zero Q-values at the end of training. There are a little over 6,500 of them and most are positive, which suggests to me that the algorithm capitalizing on what it’s learned and back propagating Q-values. Since there are more positive Q-values than negative, it’s seeking out those positive rewards like it’s supposed to.

x = [i for i in range(len(Q_values))]

q = q = list(Q_values.values())

q.sort()

p = figure(title="Q Values", plot_height=300)

p.circle(x, q)

show(p)

Anyone who has played tic-tac-toe more than a few times learns that the best opening move is to play in the center of the board. I was curious of the Q-leaning algorithm picked this up, so I looked up the Q-values for an empty board. The fifth value listed represents the center of the board, and it is in fact the greatest Q-value. Pretty cool!

[Q_values.get(((0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0), i)) for i in range(9)]

[0.5668881144477734,

0.4235054619571927,

0.4606186093821219,

0.5920863866389543,

0.755576813446845,

0.3475278319240235,

0.670954217757873,

0.49758606990650844,

0.6638934867740209]

Comments